What is Perfectionism?

In short, perfectionism is striving to be flawless in every way. And for the perfectionist, making a mistake is never acceptable. Perfectionists never see errors as opportunities for learning, but as reasons for getting down on themselves or punishing themselves.

A perfectionistic tennis player who misses an easy forehand might deliberately hit himself on the thigh with his racquet. An excellent player accepts the flub and immediately prepares for the next shot.

No matter what happens, quick recovery is key.

A potter who demands perfection of herself might throw her work-in-progress against the wall when she notices a tiny bubble forming.

It’s no surprise that perfectionists are hard to get along with. For one thing, they tend to demand the same impeccable performance from you as they do of themselves.

Imagine having a perfectionist for a boss who flies off the handle when you misunderstand his direction or dare to correct his faulty assumption.

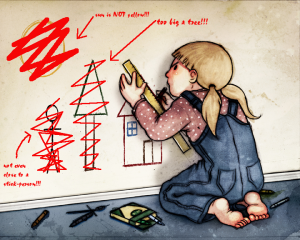

She is trying to draw the perfect scene

Staying married to a perfectionist is no walk in the park. It’s natural for couples to disagree on things–no two people have exactly the same values, standards, or preferences. But knowing that unless you capitulate to theirs, you must be ready either to do battle or bottle up your differences is no way to live. If your parent or any of your caretakers growing up were perfectionists, you are likely to suffer from deep feelings of not being good enough, not deserving praise, or lacking self-confidence, as well as crippling beliefs that limit your motivation and resilience.

Is the Notion of Perfection Well-Defined?

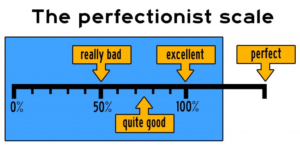

A score of 100 points out of a possible 100 points on a math test is a perfect score. So when a student strives to perform perfectly on that test, they know they must get no less than 100 points. And it’s the same for every other student who takes that test.

But more often than not, saying something is perfect does not involve a measurable characteristic or an absolute, like the perfect score on the math test (100 points and nothing less).

It only means that it couldn’t be better, as in “that grilled steak you served me on July 4th was cooked to perfection.” When it comes to grilling steak, there is no one standard for everyone. If Irv wants his steak burnt to a crisp, anything less burnt is not cooked to perfection. And if you don’t know how someone requested their meat to be cooked, when they say “it was done to perfection,” you have no idea, really, what specifically they meant, other than that they liked it just the way it was.

My point is that apart from things like math tests, when it comes to activities, computers, performances, houses, paintings, comedy routines, sonatas, vacations, pets, husbands, candidates, cars, etc. the idea of the perfect x is not well defined, if defined at all; it’s relative to the individual. If I had your “perfect husband” I’d probably divorce him. If you owned my “perfect house”, you’d complain that it’s in too small or in too remote a location.

Where Does the Drive to be Perfect Come From?

Very often, the drive to be perfect in every way, and to perform perfectly in every endeavor, begins in childhood. Abusive parents who withhold love and acceptance, (or worse–abuse their children physically, sexually, or emotionally) in effect, teach their youngsters that they are bad, not worthy, that they don’t deserve to be cherished or praised for their efforts. They tend to be harshly critical of the mistakes their kids make. They either ignore their accomplishments altogether, or only give faint praise when they do something outstanding. Typically, these parents had parents who treated them in the same way. This form of child rearing may be passed down from many generations.

The innate desire to be loved is so strong, that these children “learn to” try extra-hard to win that love and approval–to never make a mistake, to do everything perfectly–with the hope that they will win the parent over (and that the emotional, sexual, or physical abuse will stop). Psychologists seem to think that OCD (obsessive-compulsive disorder) develops in this way.

Unfortunately, children who try to be perfect in order to cope with abuse don’t simply grow out of this behavior when they become adults living on their own. They carry their perfectionistic baggage with them, along with a damaged self-concept. Too often they suffer with low self-esteem, financial problems, bad relationships, broken marriages, lost jobs, mental and physical health problems, addictions, and a deep sense of alienation.

Symptoms of Perfectionism

There are many signs that indicate a tendency towards perfectionism. The more of them you acknowledge as yours, the more likely it is that you are a perfectionist.

Your life is not an Olympic event.

Here are what I think of as some of the most common signs:

- If you think you won’t be “Number 1” in an activity you don’t participate at all. You would decline an opportunity to speak at a prestigious conference or join an elite team if you weren’t certain you’d be the best one speaking or competing.

- You don’t finish projects on time or at all. You always strive to make them better and better, even if it holds up your team members or makes you late for an appointment or meeting.

- You never tolerate making mistakes. Others may believe that “to err is human, to forgive divine,” but you think and act as if you’re a super-human who is unforgiving when you or another “miss the mark”. To the perfectionist, giving excuses for mistakes is cowardly and totally unacceptable.

- You are extremely critical. Whether of yourself or others, when things are not done they way you think they should be, you are a harsh critic. As a perfectionist, in your mind, you are the best person to define the standards for correctness. So failing to meet those standards is unacceptable. Period. End of story.

- You are never really satisfied with your own performance. You always believe you could have done better…that you should have done better, and as a result you feel mediocre at best. To a perfectionist, mediocrity is shameful.

- You have difficulty sustaining close relationships. You insist on things always being done your way (because you know what’s best), and if you don’t get your way, you sulk, or get in a bad mood, or you withdraw.

- You have difficulty relaxing and allowing yourself to relax. You believe that time relaxing is wasted, since you could be improving on a project, getting more work done better, or figuring out a better way to resolve a problem.

- You try to micromanage everything: your child’s homework, how your spouse applies their make-up or styles their hair, the way your tennis teammate serves or executes a volley.

- You feel chronically anxious and stressed out. There are so many aspects of your life that could go wrong and so many ways you could make a mistake that would prove to others you are not good enough, and certainly not perfect.

- You are impatient learning new skills. Because you hate wasting time, the longer something takes, the more frustrated you become. And the longer it takes you to learn something new, the more awkward your attempts are in the process, which makes you feel like a bumbling fool.

- You dwell on past mistakes. Your mind goes over and over what you did wrong while your inner voice harangues you about it. It’s as if you are punishing yourself so you won’t make that mistake again.

- You procrastinate on your goals. If you are unsure of how to accomplish a goal–what steps to take, what obstacles may present themselves, or whether you’ll have what you need–you delay getting started and do something else productive instead. At least you won’t waste time or risk falling short of the goal.

- You jump around from one goal to another. When you are stuck and don’t know what to do next to further the goal you are currently working on, you pick up where you left off on another goal or start something entirely new. But often, you don’t return to the original goal.

- You are hyper-organized. Because you systematically organize your closets, drawers, desk, files, books, CDs, etc. in order to facilitate getting what you need when you need it, when you can’t find something, you become easily distraught, wondering whether someone in your household took it or borrowed and returned it to the wrong place.

- You don’t ask for advice or help. To do so is a sign of weakness, dependency, or incompetence. You’d rather continue endlessly researching the problem for a solution, or table the issue, telling yourself you’ll come back to it later, and go on to something else. Or you might think that if you don’t have the answer, no one else would.

In the next blog post, entitled “Are You Proud of Being a Perfectionist? – Part 2” you will learn:

- What are the underlying fears a perfectionist suffers?

- What are the negative consequences of perfectionism?

- Why is striving for excellence, not perfection is a better strategy?